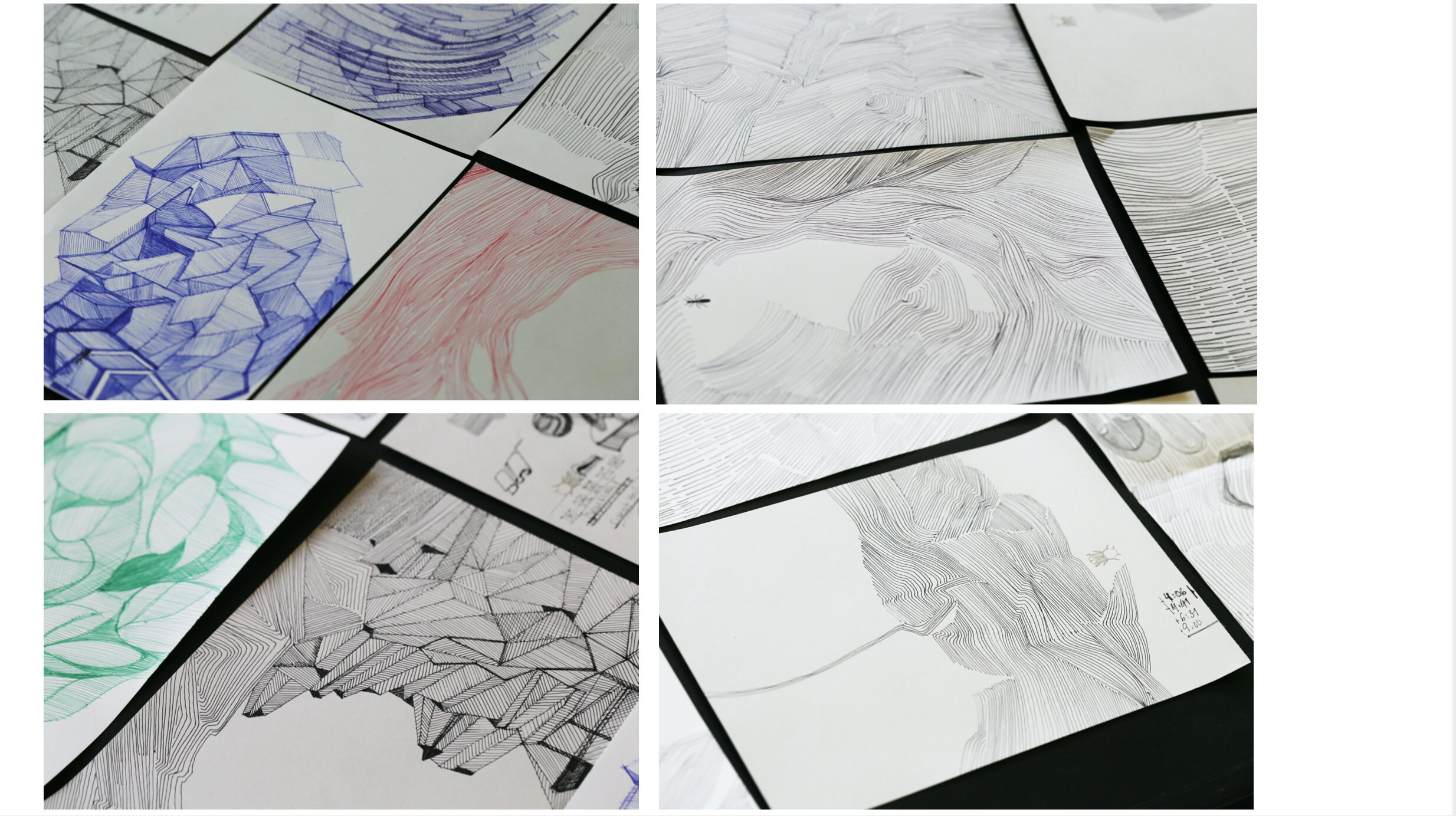

At a first glance, Victoria’s drawings are formed of rhythmical clusters, lines echoing in tandem, in collective flow. But some lines divert towards new paths, and it is the sum of these diversions that creates her intricate pictorial structures.

The same could be said of Vito’s life and career, evolving both in continuity of family paths, but also extending towards new directions, inviting new questions.She is an identical twin (and is married to a twin), an architect (and the daughter of an architect) who left her native Spain for the USA then to the UK, on journeys fueled by an insatiable curiosity towards all manifestations of form and function in everything we inhabit, make and use.

Reluctant at first about studying architecture, she soon found herself falling in love “to the point of obsession” with a discipline she considers key to thinking any form of design (“from designing an airport designing of a piece of jewelry”). Though she practices and teaches architecture, when it comes to describing her choice of profession she likes to refer to it as “working in construction”, literally and metaphorically.

Your Architectural practice is called Y, what is the reason behind this name?

My practice is called Y Architecture, as in the letter Y, the Greek Ypsilon; but it's more about why we make things work. Curiosity is my drive, learning from anything from travelling to looking and being alert whenever and wherever. In the academic world I have been teaching concept design: how you start a project. The starting point could be anything: poetry, a drawing, an action, or the brief from your client.

The letter Y echoes the Why of questioning?

Both are about the doubt beforehand. Doubt is important in order to start a conversation, to question what you are expecting from yourself, what is going to be your next step, and help you create that next step. In the studio we also use the questioning Y as a matter of working in places where the need is big, projects like a small library in Colombia or a school in Tanzania that are part of the architectural practice as well as all the other projects.

If we ‘rewind’ to your childhood years growing in Barcelona do you think the choice of clothing you wore reflected an intention to differentiate you from your twin sister, or to underline your similarities?

In Spain it was quite common to dress siblings in the same clothes. But my mother made a very clear decision. She dressed us in the same clothes but in different colors, cold colors for me, and warm colors for my sister Anna. Anna was more in reds and oranges and I was in greens and blues. I think we still go for these colors, it’s something she taught us. My mother was in Fashion in the 1970s, she brought brands to Spain that did not exist then: Cerruti, Issey Miyake, Mic Mac, Giorgio Armani. She would go to Italy, Paris or Milan, and bring clothes for us. They were very different then from what any of our friends were wearing. When we were nine or ten, we started dressing differently.

Was it a conscious decision to dress differently from that age on?

Absolutely, we would even talk about it and ask each other, “are you wearing your hair up or down today?” I was the one wearing earrings, so we would always say “Vito earrings, Ana no earrings”. We wanted to show our differences because people didn't recognize us. What happens with twins is that people recognize you as a person but they cannot allocate your name. So it was a way of claiming our identity, by claiming our names through differentiation.

Who was the first person in your entourage who embodied style for you?

It was my mother, definitely. I remember going to her room and looking at all her clothes, and seeing what she was going to wear, and watching her putting on her make up. When we were 12 or 13, I was almost embarrassed; she would wear leather trousers that nobody else was wearing at the time.

So she was Avant-garde in her style of dressing?

She had a Fashion shop called 378, and it was iconic in Barcelona. It was a small shop that my father had designed. It was all wood and smelt really nice because of the materials used. It had the ‘Wassily’ chairs. It was the first time I had seen those chairs. At 15 or 16 I started working there in the summer during the sales. I have a very definite, clear image of my mother in the 1970s: what she wore, her make- up and hairstyle, and all the catwalk shows that she organized for the collections.

Was it a clear expression of creativity and individuality on her part?

Yes, but it also came from her family. My mother's grandfather had the first textiles department store in Barcelona, from haberdashery to fabrics and clothing. My mother's side of the family was always conscious of clothing.

Did your mum keep a specific style, something distinctive?

She has an amazing hat collection from years and years. She has maybe 200 hats. She is quite well known for wearing hats. So did my grandfather, he always wore hats with a pheasant feather. That was a strong characteristic of his.

Would you say hats a running theme in the family?

Yes, on my mother's side. My father was always classic, very serious. He always wore leather shoes, never any trainers or shoes made of canvas. Always leather loafers. Even when he was flying his glider, he wore leather loafers.

Are there pieces that your mum has given you, or your family?

From my great aunt Leonor, I got a bag, a little silk velvet cape, feathers for the neck, and some accessories. From my mother some working suits, and a big coat from when she had the shop.

These are pieces that will continue down the line?

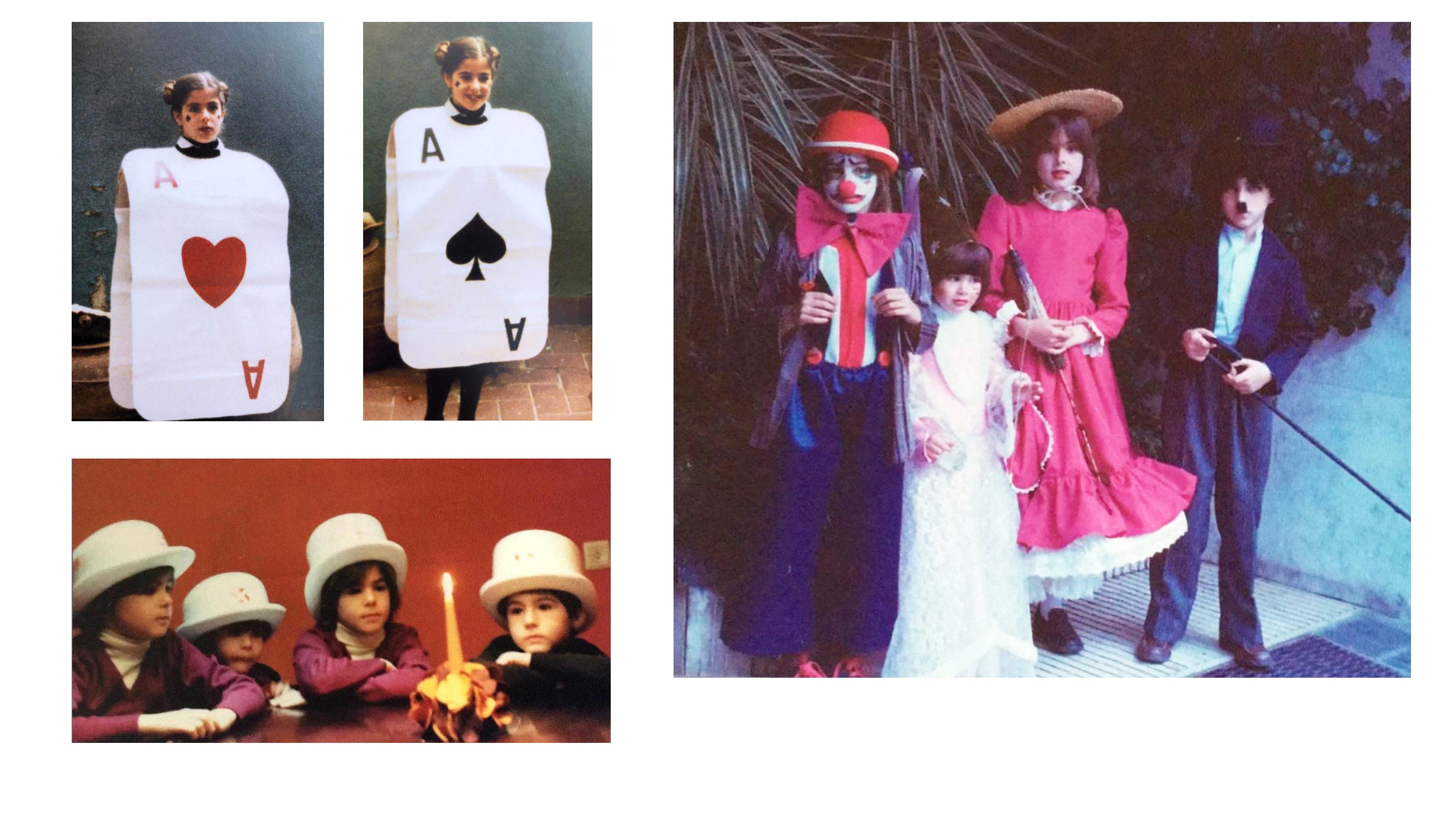

My daughter Lola loves making things, she goes to sewing lessons. She made a great piece, un-wearable because of its weight, but very interesting.When she is with her grandmother, she loves looking at her hats, trying them on. She likes dressing up. This is something my mother used to do with us, do fancy dress to go to the carnival. We had a lady called Maria who came to sew the clothes. She had a very wrinkled face, always dressed in black. She was very old, and sweet to us. When Franco died, I remember she was with us watching the TV. Maria would make us playing-card costumes. I remember the first fancy dress I wore was a ‘Champignon’ (a mushroom) and my sister was an ant.

Was there a moment as a young adult when you rebelled against this?

It was a dramatic moment when my father died. My twin sister and I got military haircuts and became kind of punk. My mother was an influence even then. She took us to Camden town in the 80s when it was kind of rough but she would get us clothes there. We had so many clothes in our family that our friends would come to our house to borrow clothes for weekends or weddings. And that stayed with me. I do the same. Clothes for me are to share.

When your mum changed career and became a film producer, did that influence you?

Yes, it was through the people who came to the house. Everyone in cinema wants to be unique in their style, they want to stand out for who they are. In architecture everyone wears black.

How did architecture impact your attitude to clothes?

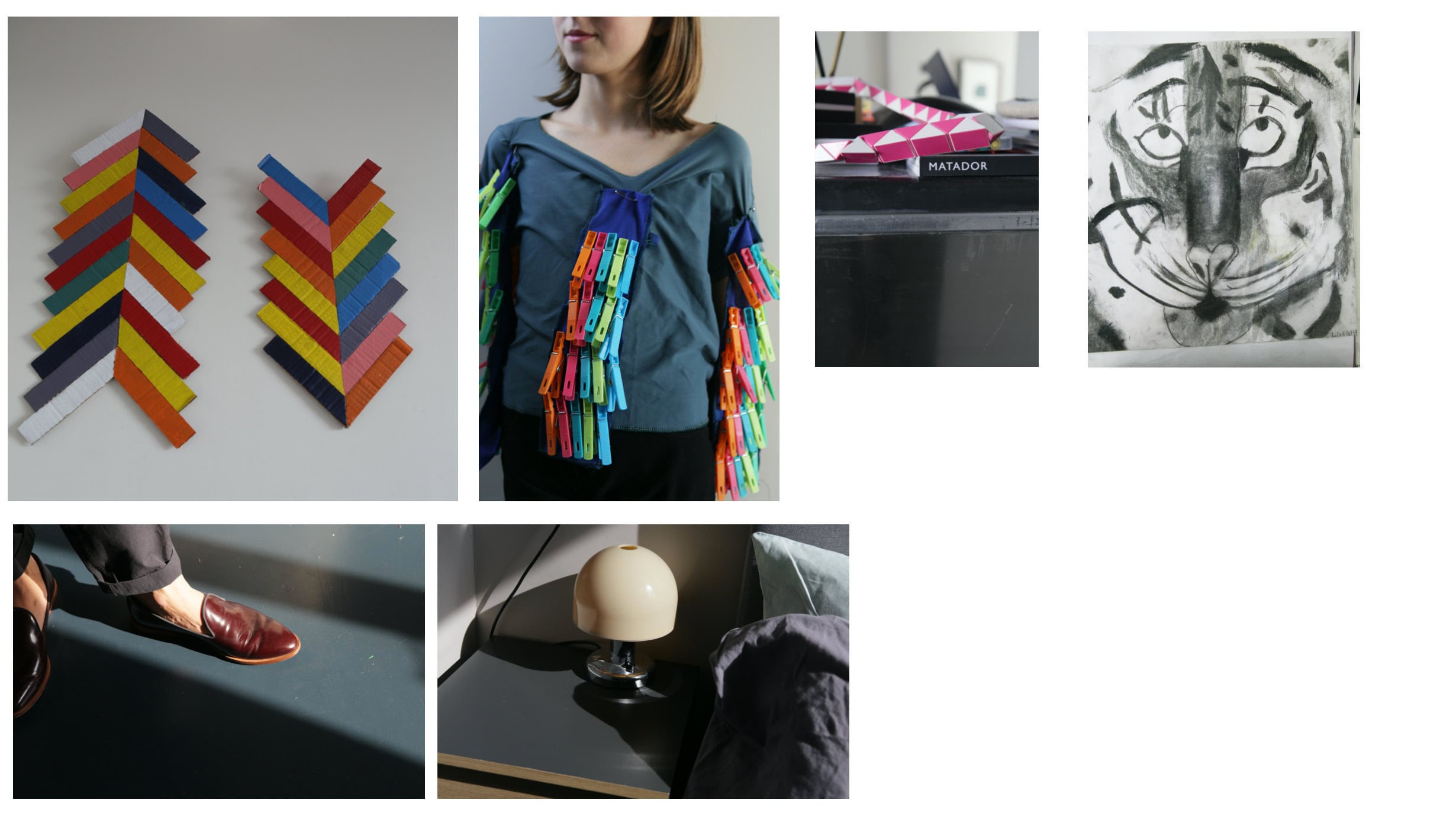

While studying architecture I made patterns for clothes, as part of understanding how everything is made. So suddenly, you start really appreciating how a piece is cut, how a pattern is made. But my taste became simpler.

Why?

It is the same as building a museum, you don't want the museum to upstage the work you are showing. That's why so many architects wear black, they don't want to think and show another identification of their design. At the same time, Architecture gives you the sense of dimension with anything. There are a lot of fashion designers who have trained as architects.

One could say Architecture is about creating spaces for bodies, clothing design about creating shells for our bodies; are there parallels?

Yes, it's all about scale. When I taught Architecture with Miralles and Mias, we used to ask the students to wear their architectural models, and do a catwalk. Where would you put that model on your body? A lot of the students used to relate to that, the way you would wear something in order to be creative. The experience can be as if you were wearing the space. Some wore the architectural models as hats. Working the scale, taking a piece of textile for example, and making it bigger in scale to become a building or taking that piece of textile and putting on the body. It was the same design in different scales and functions.

Are your drawings more about rhythm or structure?

The drawings, come alive by themselves, I start doing the lines that have a movement. When you add them, it becomes a kind of foldable space. The space you see when your eyes are further away grows in the process. I am interested in what has been created behind the space that the lines have formed, a bit like the edges and the air in between the skin and the material: the drawing’s own ‘behind space’.

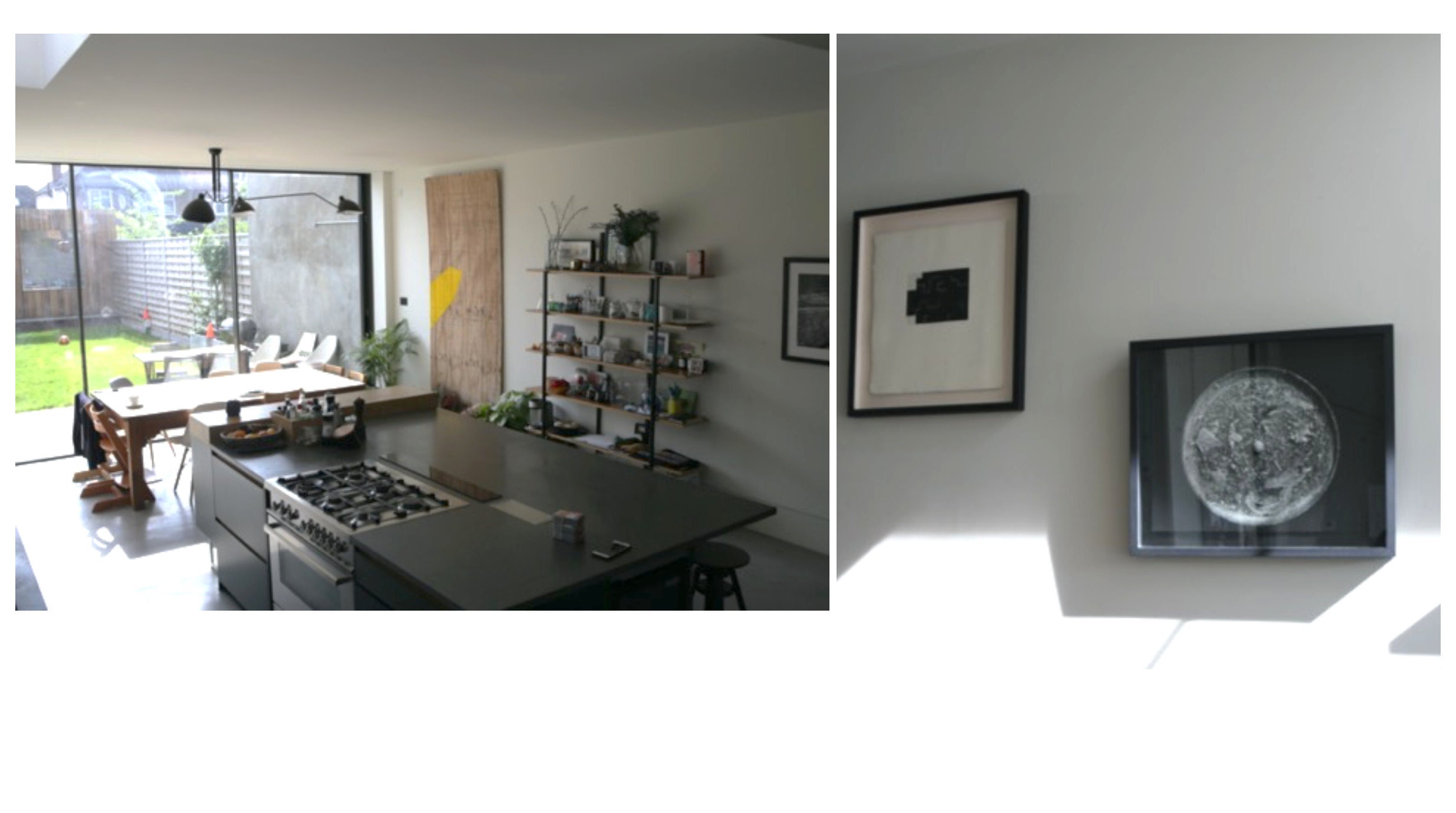

Is your choice of clothing an extension of your choice of objects, art, and design around you?

I believe choice for design and clothes is all part of the same identity. Color is incredibly important, and there are some colors I am attracted to for clothing and for my design, and some colors that are a ‘no-no’ for me. But I think that sometimes you dress up more with accessories when you are trying to show a certain mood.

Are you drawn to accessories because they are more like objects?

Yes, definitely, accessories are like the lighting or furniture in a house. So you have the structure of the house to start with, the equivalent to what you are wearing for example, a skirt or a dress, a blouse. But then with the lighting, furniture or a painting or even china, a flower jug, you show more your intimate personality and mood. I am looking at the lamp in my studio, it can be something you can wear. I don’t have many clothing pieces that are very extravagant, but I have some extravagant accessories. Accessories can reflect more of a mood; clothes are more of a constant.

If we think of the content of our wardrobes as a diary of our life and its different phases, changes, and you had to do a graph of it, what would it look like?

I see boxes in a row, with different dimensions, some bigger, some smaller. Some have no functional use but have a smell. I have two jumpers from my grandfather and one from my father. He died in 1983 but I still have his jumper because of its scent. I also have clothes from my children that I cannot let go of. They are in boxes that are closed but that I can go back to when I need to. There are also Fancy-dress clothes in a large box. This box has clothes with so many memories, parties.

Sounds like a metaphor of memory. It is, it’s like a visual representation of time, I have a clear drawing of it in my head.